Story

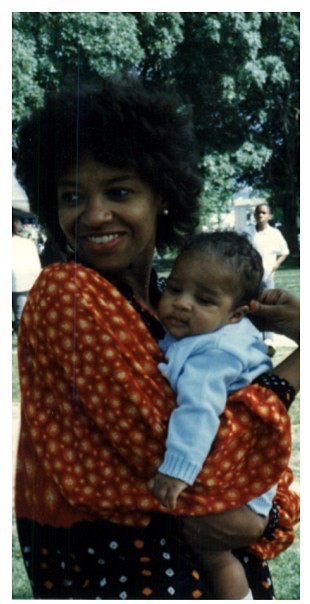

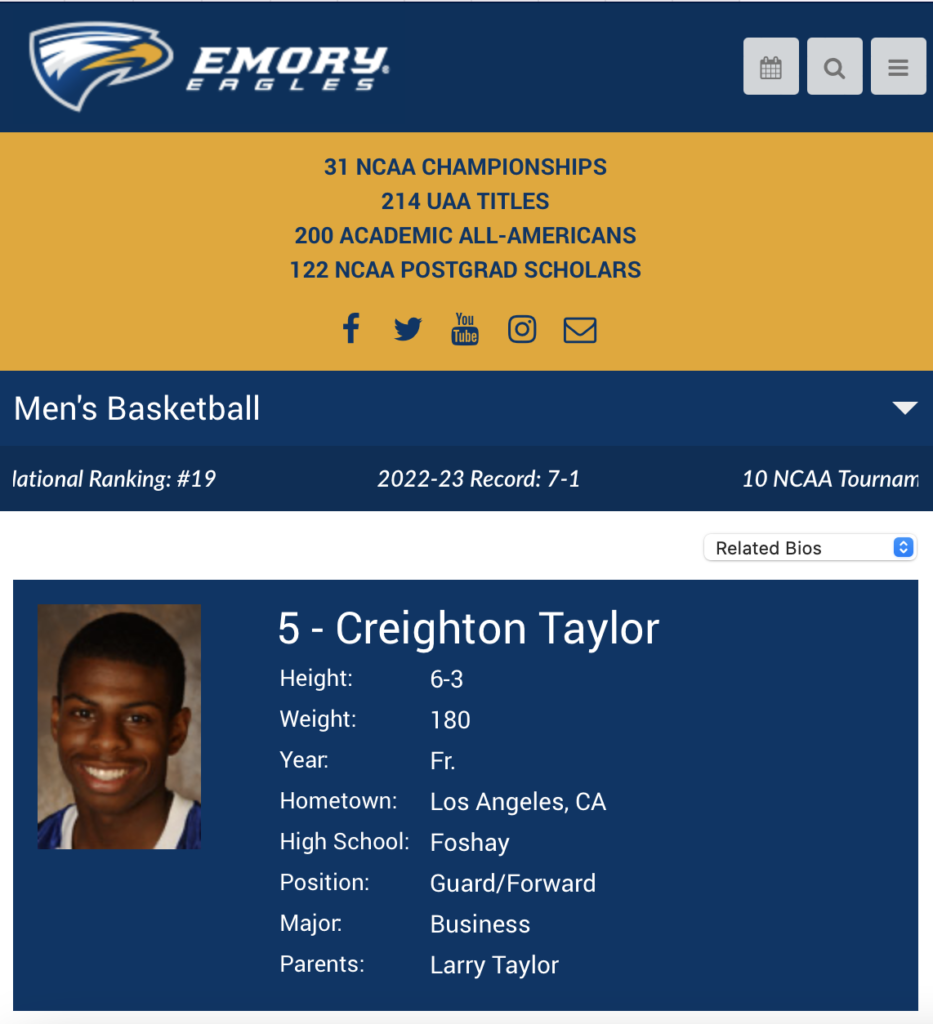

Born in Hollywood CA, I knew I was destined to become a star. Just like every small child in the 80s/90s, I practiced my Michael Jackson moves while looking at myself in the mirror. When I was a bit older, I took up basketball and drawing. However, my outlook on life changed when my mom suddenly passed away from lung cancer when I was 12. I suddenly threw all my creative energy into teaching myself piano. In high school, administrators held students captive against their will as I performed piano pieces like Claire De Lune, Maple Leaf Rag, and Pine Apple Rag during student assemblies. At the end of my performances, I would bow like they paid good money to see me. Around the same time, I grew to be an athletic, 6’3” 180 pounds basketball playing machine. It was around this time that I began to make my first choice motivated by “rebellious pioneering”. I didn’t want to be another black ball player. So, even though I was recruited to play basketball at Emory University, I attended because of its stellar academic reputation. I’m ambivalent about this “rebellious pioneering” mental model until this day, because as you will see in this story, it will rear its ugly head again.

Born in Hollywood CA, I knew I was destined to become a star. Just like every small child in the 80s/90s, I practiced my Michael Jackson moves while looking at myself in the mirror. When I was a bit older, I took up basketball and drawing. However, my outlook on life changed when my mom suddenly passed away from lung cancer when I was 12. I suddenly threw all my creative energy into teaching myself piano. In high school, administrators held students captive against their will as I performed piano pieces like Claire De Lune, Maple Leaf Rag, and Pine Apple Rag during student assemblies. At the end of my performances, I would bow like they paid good money to see me. Around the same time, I grew to be an athletic, 6’3” 180 pounds basketball playing machine. It was around this time that I began to make my first choice motivated by “rebellious pioneering”. I didn’t want to be another black ball player. So, even though I was recruited to play basketball at Emory University, I attended because of its stellar academic reputation. I’m ambivalent about this “rebellious pioneering” mental model until this day, because as you will see in this story, it will rear its ugly head again.

During my first semester at Emory, I got a 1.65 GPA. I just didn’t know how to effectively study. By contrast, during my time at Los Angeles Unified School District, my GPA was over 3.5 and I rarely needed to study. The next two semesters, I essentially slept in the library, learning how to speed read and take tests quickly. I received a 3.3 the next semester, a 3.6 GPA the semester after that, and held a 3.5 for the rest of my time at Emory. Due to my need to focus and my lack of care about my basketball career, I quit the basketball team after my first year and picked up a music major (in addition to business). In my second year of college, I received my first official music lessons. Things felt like they came full circle when I performed Prelude in G Minor Op 23 No 5 by Rachmaninov at my graduation ceremony. I received a standing ovation and a huge hug from my grandfather who had driven ten hours to attend. This was a particularly touching moment for two reasons. First, as an African-American man, my grandfather was particularly proud to see his eldest grandchild graduate from a great institution. Second, my grandfather was the father of my mother, who was the inspiration for me beginning to play the piano.

Graduating meant it was time for adulting. But adulting is hard when you graduate in 2008 at the peak of the credit crisis seeking a job in finance. I had already spent years studying finance at this point because I was good with numbers, finance had been the hot profession, and there were few negroes in the profession. 500 applications in, I landed a job at Western Asset Management (WAMCO) as a fund administrator. WAMCO was a supposedly “safe” employer because they had $640 billion assets under management, had a “safe” investment focus, and had 1,000+ employees. Yet, a year later I was laid off because they invested heavily in mortgage-backed securities. I passed two CFA exams back-to-back while at WAMCO, impressing a partner of Rochdale Investment Management. A few months later, he hired me to support the sales and marketing process. As opposed to WAMCO, which invested money for large institutions, Rochdale invested money for individuals; rich people. Rochdale went from $2.2 billion under management to over $6.5 billion and it was sold to City National Bank during my time there. I got perfect performance reviews during my time there: analyzing portfolios, creating pitch decks, helping with sales strategies, training new hires, and automating repetitive tasks in the office with a Microsoft Excel scripting language. I applied to a number of business schools, and got into Harvard. I’m ashamed to say that I was instantly drunk at a nearby bar mid-workday after receiving the news.

Once on campus, I quickly realized that getting in is far more difficult than graduating. Harvard Business School (HBS) teaches exclusively via the case method, meaning that grades were 50% class participation: discussing a case previously read (i.e., if you said an insightful comment every two classes, you shouldn’t be in the bottom 10% of the class) and 50% final case analysis (i.e., you spend a few hours reading a case and providing a written analysis on how you’d solve the case). The first year experience is fun because they divide the 900-person class into 10 sections. Each section competes with one another across a variety of sports and activities. I was Section A, and our mascot was a panda bear. By far, the most learning I experienced was from other people: meeting people from all walks of life, learning how they think, and learning their background. The second year was a struggle as I thought about switching out of finance entirely. After writing a paper on the future of financial technology, and starting to write a book, I realized that there was a large gap for non-rich populations to earn enough income so that they can begin to effectively invest. I worked on addressing this problem when I graduated, and then for many years afterwards. In fact, I still work on it today.

How does one solve such a huge problem in 2014? One builds an app, of course. And that’s exactly what I did. The only problem? I didn’t know how to build an app. Since I knew I wanted to iterate on the solution, I didn’t hire developers, I learned to code. My life became hours upon hours of watching YouTube videos, downloading GitHub projects, and scouring StackOverflow to learn the coding language Swift. Months later, my app was approved, and I announced it to the world! I got roasted so hard y’all, my feelings were hurt. Buttons didn’t work, the visual style was repulsive, and people were confused about what to do. After some iterating, I was able to raise an angel round of funding, and hire two people, but my inexperience was failing everyone – from product management to software development to design. There were also some fundamental flaws with assumptions on whether the target users would pay/use the product. After 1.5 years, I wound the company down. But now I had a new and particular set of skills. I built multiple apps, and began conducting product management and software engineering consulting. I joined Fitspot as Head of Product, a $1MM funded Techstars company. And then I regrettably joined Emmasson as Head of Product, a company that fraudulently claimed it raised $175MM and failed to pay 20+ employees and stakeholders. After a while, I realized that I couldn’t stay away from the problem Compass 1.0 addressed, and returned to working on different iterations of the solution. Guided Compass was born. Instead of only focusing on youth directly, I charged a subscription fee to the organizations that serve youth for access to the software. I started it as a single founder with far more experience than before. After many hurdles, it now generates enough income for me to live comfortably.

Highs:

- Graduating from Harvard University with an MBA degree

- Passing the final CFA exam of three exams

- Performing Rachmaninoff Prelude in G Minor on piano at graduation ceremony

- Getting recruited to play basketball for the Emory University basketball team.

- Learning that the company I worked at was being acquired (it was a very small team)

- Learning to code and launching my first mobile app (Compass 1.0)

- Completing a marathon

Lows:

- Sleeping in a car with Mom for a summer because we didn’t have a place to live

- My Mom passing away from Cancer four days before I became a teenager

- Getting laid off from Western Asset Management, my first job out of college

- Failing to grow Compass 1.0 into a successful business

- Joining and helping to build a product for Fyre Festival-like company Emmasson

- My car getting totaled from catching on fire a few minutes after I parked it